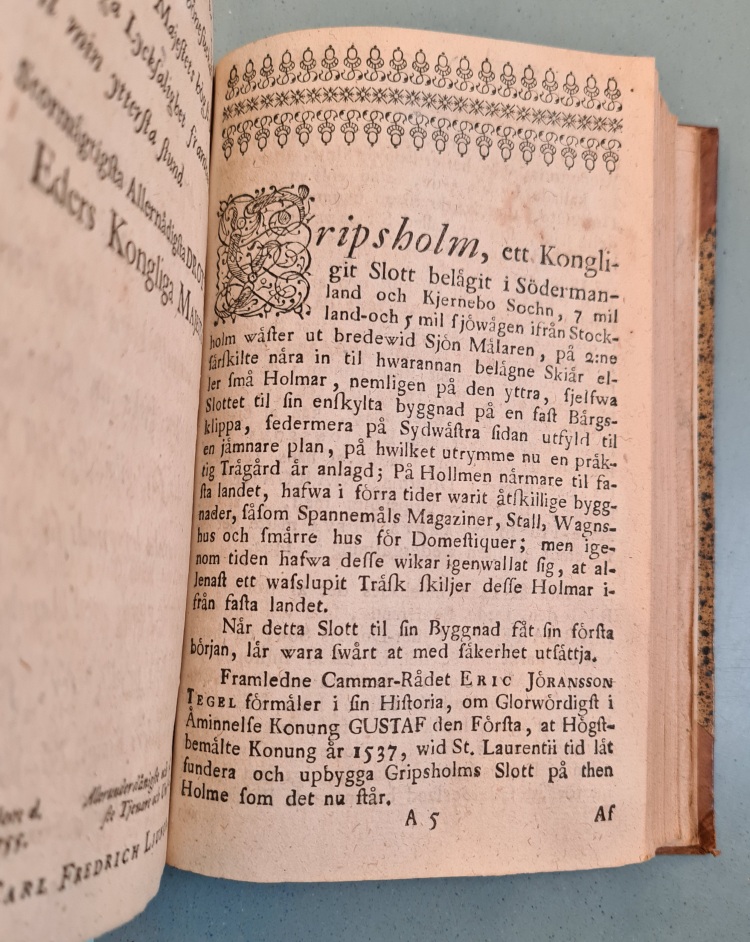

Stormägtigsta Allernådigsta DROTTNING! Så inledde Carl Fredrich Ljungman, slottsförvaltare på Gripsholm, sin första vägledning över Gripsholms slott år 1755. I den vackra 1700-talsskriften kan man läsa om slottet och dess historia fram till och med änkedrottning Lovisa Ulrika. Skriften avslutas med en prydlig lista över 308 stycken ”Contrefait och Schillerier”, noggrant numrerade och beskrivna: så såg innehållet i konstsamlingen på Gripsholm ut vid mitten av 1700-talet.

När Gustav III kom till slottet för första gången 1772 beskrev han det som omodernt och förfallet. Ändå blev han förälskad, det var som att ”vandra bland sina fäder” skrev han. Förälskelsen skulle leda till ett av de stora skiftena i samlingens historia och till ganska mycket arbete för Ljungman som var den som behövde hantera det förändrade samlandet i praktiken. I Gustav III:s händer transformerades slottet till ett slags monument – över honom själv och över hans två största idoler: Gustav Vasa och Gustav II Adolf. Syftena bakom samlandet förändrades och samlingen växte. Gustav III:s befallning att flytta målningarna av Karl XI:s rådsherrar från Drottningholm till Gripsholm betraktas ibland som den nationella porträttsamlingens informella startskott, eller i varje fall som en betydelsefull brytpunkt i samlingspraktiken. Ljungman själv var kvar på båda sidor om förändringen.

1790 publicerade Ljungman en ny uppdaterad beskrivning av slottet och samlingen, framtagen på direkt order av Gustav III som förmodligen ville visa de förändringar han åstadkommit. Eller som Ljungman själv skriver 1790: Det nya som häruti omröres är tillkommit genom Eder Kongl. Maj:ts egen höga försorg, och skall bära evigt vittnesbörd, så väl om Eder Kongl- Maj:ts Kärlek för den Store Konung GUSTAF den Förste, hvars åminnelse gjort Gripsholms Slott för Eder Kongl. Maj:ts behagligt, som Eders Kongl. Maj:ts höga smak för Vitterhet och fria konster.

Gustav III hade sina syften bakom samlandet. De som föregått honom hade andra syften liksom de som samlat därefter. Att lägga de båda beskrivningarna från 1755 och 1790 bredvid varandra, och bredvid senare kataloger, gör detta särskilt tydligt. Inte minst låter det oss komma nära samlarna – både de som beställde och de som hade att hantera deras beställningar. Båda deras berättelser är viktiga för att förstå.

A brief description of Castle Gripsholm 1755 and 1790

”Allmighty Merciful QUEEN!” With those words Carl Fredrich Ljungman began his description of Castle Gripsholm, written in 1755. The beautiful publication from the 18th century presents the castle and its history up to his own time under the widowed queen Lovisa Ulrika. The major part of the guide consists of a list of 308 “Contrefait & Schillerier” (paintings), all numbered and described: This is what the art collection at Gripsholm looked like in the middle of the 18th century.

When king Gustav III arrived at the castle for the first time in 1772 he described it as unmodern and in need of repair. But regardless of this he fell in love, it was like “wandering among ones fathers” as he wrote himself. This love would lead to one of the major shifts in the history of the castle and to quite a lot of work on Ljungmans behalf, who probably was the one who had to handle the changes. In the hands of Gustav III the castle was transformed to a kind of monument – over himself and over his two biggest idols Gustav Vasa and Gustav II Adolf. The purposes behind the collecting had changed and the collection grew. Gustav III:s decision to move the paintings of the chancellors of Karl XI from Castle Drottningholm to Gripsholm are sometimes viewed as the informal start of the National Portrait Gallery, or at least as a very important changing point in the practices of collecting. Ljungman himself worked on both sides of the changes.

1790 Ljungman published a new and updated description of the castle and the collection, directly ordered by Gustav III, who probably wanted to show the changes. Ljungman wrote: “The new that are here told has come to be by Your Royal Majesty’s own work, and shall be an eternal witness, as well as of Your Royal Majesty’s Love for the Great King GUSTAF the First, whose memory has made Gripsholms Castle so dear for Your Royal Majesty, as well as Your Royal Majesty’s great taste for learning and the free arts.”

Gustav III had his own purposes behind his collecting. Those who preceded him had other purposes just as those who succeeded him. To place the two guides or descriptions beside one another, and beside latter catalogues, makes this particularly evident. It also enables enable us to come close to the collectors – both the ones that actually could decide and the ones who had to handle the decisions. To be able to understand we need both their stories.